The waggle - and so much more

I thought it would be interesting to put together some interesting facts about honeybees, since what we are doing involves them greatly.

Field bees communicate the location of flowers to other bees by “dancing.” They signal to other bees about flowers’ distance and direction by walking in circles and by wagging their hindquarters. The term “beeline” refers to the fact that once done collecting nectar, bees fly directly to the hive, using the fastest, straightest path possible.

Figure-Eight-Shaped Waggle Dance of the Honeybee (Apis mellifera). A waggle run oriented 45° to the right of ‘up’ on the vertical comb (A) indicates a food source 45° to the right of the direction of the sun outside the hive (B). The abdomen of the dancer appears blurred because of the rapid motion from side to side.

A healthy queen can lay over a million eggs within her four-year life span.

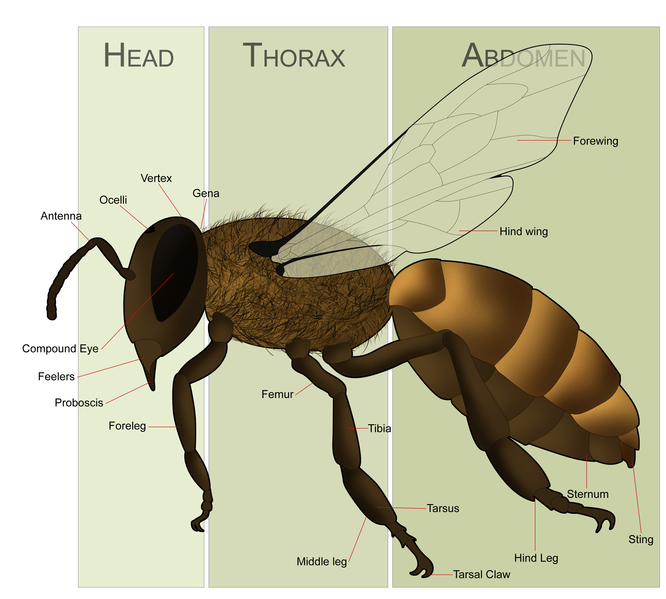

Bees have thousands of barbed hairs on their bodies that collect pollen that is then dusted off into “pollen baskets” located on the outsides of their back legs.

Honeybees can see ultraviolet light, which allows them to sense which flowers are full of nectar. They also have three small eyes at the tops of their heads that act as light sensors, allowing them to see the sun even when it’s hidden behind clouds.

Nectar collected to make honey is stored in a “honey sac,” which is located along the bees’ digestive tracts in front of their midgets, where food digestion takes place. Nectar is stored in the sac until the bee returns to the hive and passes it off to a hive bee for processing. Honeybees forage in about a 3-mile radius.

One honeybee will produce 1-2 teaspoons of honey in its lifetime.

A honeybee’s lifespan is 34-36 days.

A honeybee beats its wings about 230 times per second.

The honeybee flies at about 15 miles per hour, they fly slightly faster when leaving the hive empty and slower when returning with nectar, pollen or water.

Honeybees use there antennas to detect smells in the air, there sense of smell is so impressive that scientists were able to train a species of wasps to find buried land mines.

Life cycle

As in a few other types of eusocial bees, a colony generally contains one queen bee a fertile female; seasonally up to a few thousand drone bees or fertile males and a large seasonally variable population of sterile female worker bees. Details vary among the different species of honeybees, but common features include:

1. Eggs are laid singly in a cell in a wax honeycomb produced and shaped by the worker bees. Using her spermatheca, the queen actually can choose to fertilize the egg she is laying, usually depending on what cell she is laying in. Drones develop from unfertilized eggs, while females (queens and worker bees) develop from fertilized eggs. Larvae are initially fed with royal jelly produced by worker bees, later switching to honey and pollen. The exception is a larva fed solely on royal jelly, which will develop into a queen bee. The larva undergoes several moltings before spinning a cocoon within the cell, and pupating.

2. Young worker bees clean the hive and feed the larvae. When their royal jelly producing glands begin to mature, they begin building comb cells. They progress to other within-colony tasks as they become older, such as receiving nectar and pollen from foragers, and guarding the hive. Later still, a worker takes her first orientation flights and finally leaves the hive and typically spends the remainder of her life as a forager.

Waggle

3. Worker bees cooperate to find food and use a pattern of “dancing” (known as the bee dance or waggle dance) to communicate information regarding resources with each other; this dance varies from species to species, but all living species of Apis exhibit some form of the behavior. If the resources are very close to the hive, they may also exhibit a less specific dance commonly known as the “Round Dance”.

4. Honey bees also perform tremble dances, which recruit receiver bees to collect nectar from returning foragers.

5. Virgin queens go on mating flights away from their home colony, and mate with multiple drones before returning. The drones die in the act of mating.

6. Colonies are established not by solitary queens, as in most bees, but by group’s known as “swarms“, which consist of a mated queen and a large contingent of worker bees. This group moves en masse to a nest site that has been scouted by worker bees beforehand. Once they arrive, they immediately construct a new wax comb and begin to raise new worker brood. This type of nest founding is not seen in any other living bee genus, though there are several groups of Vespid wasps, which also found new nests via swarming (sometimes including multiple queens). Also, stingless bees will start new nests with large numbers of worker bees, but the nest is constructed before a queen is escorted to the site, and this worker force is not a true “swarm”.

Winter survival

In cold climates honeybees stop flying when the temperature drops below about 10 °C (50 °F) and crowd into the central area of the hive to form a “winter cluster”. The worker bees huddle around the queen bee at the center of the cluster, shivering in order to keep the center between 27 °C (81 °F) at the start of winter (during the brood less period) and 34 °C (93 °F) once the queen resumes laying. The worker bees rotate through the cluster from the outside to the inside so that no bee gets too cold. The outside edges of the cluster stay at about 8–9 °C (46–48 °F). The colder the weather is outside, the more compact the cluster becomes. During winter, they consume their stored honey to produce body heat. The amount of honey consumed during the winter is a function of winter length and severity but ranges in temperate climates from 30 to 100 lbs.

Pollination

Species of Apis are generalist floral visitors, and will pollinate a large variety of plants, but by no means all plants. Of all the honeybee species, only Apis mellifera has been used extensively for commercial pollination of crops and other plants. The value of these pollination services is commonly measured in the billions of dollars.

Honey

Honey is the complex substance made when the nectar and sweet deposits from plants and trees are gathered, modified and stored in the honeycomb by honeybees as a food source for the colony. All living species of Apis have had their honey gathered by indigenous peoples for consumption, though for commercial purposes only Apis mellifera and Apis cerana have been exploited to any degree. Humans sometimes also gather honey from the nests of various stingless bees. 1 worker bee will produce about one to two teaspoons of honey in its entire lifetime. The accumulation of such enormous stores of honey in a hive in one day are due to there being anywhere from 20,000 to 80,000 + bees in the hive at one time – all doing the work of nursing brood, cleaning ‘house’, guarding stores, and foraging for nectar. A bee goes out to forage for honey, visiting 100 flowers per each trip out of the hive, covering about a 3-mile radius, making approximately 10 trips per day, for each day of her whole life – as a forager. Her life is only about 4 weeks. (34-36 days) She literally works herself to death… for one to two teaspoons of honey.

Beeswax

Honeybees produce beeswax from the underside of there abdomens. They have to eat 17.5 pounds of honey to make .5 pounds of beeswax.

Worker bees of a certain age will secrete beeswax from a series of glands on their abdomens. They use the wax to form the walls and caps of the comb. Beeswax gets its wonderful natural color and honey-like fragrance from the pollen and nectar of the flowers the bees are pollinating. The color often depends on what particular crop the bees are pollinating. Dark berries, like blueberries or blackberries, will derive a much darker, browner wax. Clover, however, will result in a brighter, golden tone.